Hellschreiber – or the devil’s writing

Article by HE Translations marketing representative Mike Gayler

Those of a certain age will remember both telexes and fax machines. If you are a mere youngster, let me try to explain:

Telex was a way of sending typed messages from one ‘typewriter’ to another (please tell me you do vaguely know what a typewriter is? No? OK – let’s say from one keyboard to another).

The sending operator typed the message into his keyboard and it was sent through the phone system to the receiving keyboard, where the message would be printed out. How, you ask, did it get to the right place? Every keyboard had its own identification – originally not a number, but a name. Names like ‘Interflora’ , ‘Interpol’ or ‘Insurance’.

Fax? You must have seen a fax, surely? That sheet of paper with a good copy, maybe a bit blurred, of exactly what had been sent at the other end, images and all (assuming the office junior had put the paper in the right way round!)

Telex – or more accurately teleprinter transmission systems – were developed in Germany in the mid 1920s becoming a service of the Reichspost within 10 years. The technology rapidly spread around Europe, and by 1945 was in use worldwide using shortwave radio links – known as Radio Teletype (or RTTY). The messages were generally prepared on punched paper strips that were fed into sending devices attached to the keyboard. Telex has all but disappeared from modern offices, although some legal services still use a modern version for secure communications.

Fax, surprisingly, has a much longer history, having been first invented in Scotland by Alexander Bain in the mid 1840s, and brought to popular use by both English and German developers in the early 1900s. Fax was an early use of the new, modern radio technology, with the French sending a faxed newspaper into homes in the 1930s. In the 1940s the Western Union company had even fitted fax receivers into vehicles in the USA. It wasn’t until the 1960s that the ‘modern’ fax machine, attached to a telephone line, was introduced. Fax is still in use for some legal and medical services, but is rapidly being replaced by email which is much more secure.

Rudolph Hell (1901 – 2002) successfully invented a machine that combined the best attributes of both teletype and fax systems but with less moving parts and greater reliability. Hell was an inventor from Bavaria who by the age of 24 was operating a television station in Munich.

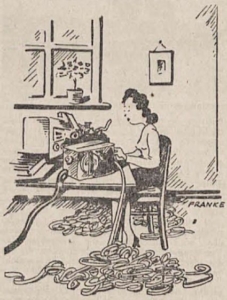

Hellschreiber image, reproduced with kind permission by Frank Dörenberg

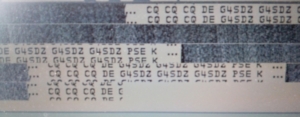

Hell’s machine – the Hellschreiber – sends text as lines of vertical columns in a grid which can be easily read on suitable equipment by the recipient – special characters or different typefaces (non-Western, for example) can be transmitted, unlike telex or RTTY, but, not the pictures that can be sent by fax. The sender uses a keyboard on a Hell machine to transmit the message, and the recipient receives the message in a strip format on paper, or on a screen.

The Hellschreiber system lends itself to both wire and radio transmission (the Wehrmacht even used it with light signals – the Lichtsprechgerät or light telephone). The main commercial use of the Hellschreiber system was for sending stories from journalists to newspapers, and sometimes even to public news subscribers. This Presse-Hell system removed the need for trained morse operators, did away for the possibility of error, and allowed for unattended reception of reports. Presse-Hell started as a German service in the 1930s quickly coming into use world-wide, but falling out of favour in the late 1950s, with the last reported commercial use in 1982. With Hell, and Presse-Hell systems being reliable and very tolerant of poor radio reception they were also used by a number of other organisations with worldwide offices. This degree of tolerance also allowed Hell and Presse-Hell systems to be used in German Navy Submarines with good effect.

The girl at the Hellschreiber” – cartoon in the Litzmannstädter Zeitung newspaper (1943), reproduced with kind permission by Frank Dörenberg

A comprehensive history of Presse-Hell with description of its use and pictures of the machines and messages can be found here.

The Hell system is safe today in the hands of a worldwide group of licenced amateur radio enthusiasts who transmit Hell signals worldwide using both original equipment and modern computers to generate the messages.

The ‘Feld Hell Club’ is the main organisation promoting this aspect of an already fascinating hobby with awards for making Hell contacts in multiples of countries, or regions. The predominant type of Rudolph Hell’s method in use today is Feld Hell which was developed for portable military use. Feld Hell is a very good compromise Hell system for amateur radio use with a fair number of original machines still around and serviceable.

Using Feld Hell on shortwave amateur radio frequencies is a niche activity and schedules are often arranged by operators in advance. The signal is very distinctive in tone, and can ‘spread out’ across the available radio spectrum, making it a little anti-social in the eyes (or ears) of amateur morse code and radio teletype operators. However, good reception of signals from stations with very modest antennas and low power transmitters is very possible, and gives hope to those licensed operators on limited budgets or with no space for big aerials.

The author transmits Feld Hell signals from his home in Leicestershire, mainly on 7Mhz with transmission powers generally below 20w to a very simple dipole aerial. The Hell signals come from an old laptop running software called FLDigi on the back of Linux Mint. Contacts have been made with other Feld Hell stations all over Europe.

Further reading

- The main resource for those interested in all things Hell related is the web page at www.nonstopsystems.com/radio/hellschreiber.htm

- Other background information is at en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hellschreiber and en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rudolf_Hell

- The history of Telex and Radio Teletype can be seen at en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Telex and en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Radioteletype

- The fascinating history of Fax is at en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fax

- The Feld Hell Club website is at sites.google.com/site/feldhellclub/

- The Radio Society of Great Britain is the national organisation for radio amateurs at rsgb.org/

- Rudolf Hell obituary | The Independent (2002)

- Inventor of the Fax Machine Turns 100 – DW – 12/19/2001