Translating the Madhouse Effect into German

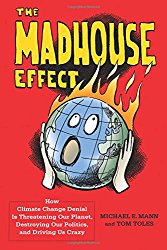

We are currently translating The Madhouse Effect, a popular and very readable illustrated book on climate change, by leading climate scientist Michael E Mann and cartoonist Tom Toles. The book, originally published in 2016, was motivated by the authors’ urgent desire to clear a fog of manufactured and self-interested climate scepticism around the greenhouse effect. The full original English language title is The Madhouse Effect: How Climate Change Denial is Threatening Our Planet, Destroying Our Politics, and Driving Us Crazy. The German translation is a collaboration between Herbert Eppel and project initiator Matthias Hüttmann.

So far the best working title for the German language translation has been Der Tollhaus-Effekt. The English word madhouse suggests a place of chaos, lunacy and foolishness, as well as clinical mental illness, but not fun or enjoyment. Tollhaus might suggest to an Anglophone a toll-taking station, such as in the book The Phantom Tollbooth, but the German adjective toll actually means “splendid” or “super!” The compound word Tollhaus can indeed describe a madhouse, both in the colloquial sense of a locus of lunacy, and in the technical sense of a mental hospital, but in the present day some businesses are using this word as a name for a themed safe play area or nightclub. That might sound a bit like the innocuous English term funhouse, so in this case the book’s cover illustration may ease the translator’s task by hinting at what sort of madness the book concerns.

As well as admirably exploring the pressing scientific and social issues for the layman, The Madhouse Effect also looks at how language itself has been altered by shadowy paid lobbyists and professional astroturfers. Michael Mann explains how the scientific method works and its need for rational enquiry, hypotheses, tests, and evidence. He then continues, “Unfortunately the term ‘skeptic’ has been hijacked, especially in the climate change debate, to mean something entirely different. It is used as a way to dodge evidence one simply doesn’t like.”

So, when the evidence is that one’s house, or world, is on fire, it is hard to see why anyone would want to reject the evidence; unless, of course, they are heavily insured against loss, and have another place ready to move to. So perhaps they need to read this book.